Reykjavík · September 9th, 2016

Uncharted Waters

How the Norse found the New World

The Northern reaches were the last parts of the old world to be permanently populated. It is not hard to understand why; the further North you go, the harsher the climate and harder the struggle for a comfortable life becomes. One would think this would put a limit to the adventurousness, but that doesn’t seem to be the case for our ancestors. When all of Norway was discovered and populated, however sparsely, the search for new land began. So the Vikings built great long ships and set sail, hoping to find new lands in the sea.

The first piece of real estate they made their own, in the 8th century, was Shetland, some 350 kilometres from the west coast of Norway. Only decades later, Norse people went to the Faroe Islands, approximately twice as far from home. Then in the middle of the 9th century, and again twice as far from home, they set foot on the shores of Iceland. None of these places were truly discovered by the Norse, however. A few Celtic people, perhaps mostly monks, were already living on these islands when the Vikings settled. Their fate is unknown.

It was on Iceland that the age of true discovery started. The Norwegian Þorvaldr Ásvaldsson from Jæren (a first cousin twice removed of Naddoðr, according to the saga of the first Norwegian to set foot on Iceland) was banished for manslaughter in mid 10th century. He moved to Iceland with his family to start a new life. But after a while, the family was in trouble again. His son Eiríkr killed several men around 982, and was sentenced to three years of exile. Like his father, he fled his country. There were rumours about land far away to the west of Iceland, accidentally discovered almost a century earlier by a man named Gunnbjǫrn Ulfsson. After him, one Snæbjǫrn Galti had led an expedition to this unknown land, which ended in disaster. So Eiríkr hinn rauði (Eric the red, as he is known as in English) set sail for a mysterious and little-known land that some said were nothing but a myth. But land he did find, and a big one at that. He spent his three years of exile exploring the vast land-mass, and returned with stories of the fabled country. Being a good marketer, he deliberately gave the land a more appealing name than Iceland. “People would be attracted to go there if it had a favourable name”, it says in the saga later written about his life. He knew that a successful settlement in Greenland would depend on the support of as many people as possible. His salesmanship proved successful; people were convinced that Greenland held great opportunity. 25 ships left Iceland, though only 14 reached its destination. The rest sank on the dangerous 1500 kilometre long journey to the new land in the west.

The Norsemen built two settlements on the south-western coast, one close to the modern day capital Nuuk, another one near what is now Qaqortoq. Temperatures were higher on Greenland then, allowing for agriculture and animal husbandry. The settlements grew to a peak population of 5–6000 people in the 14th century.

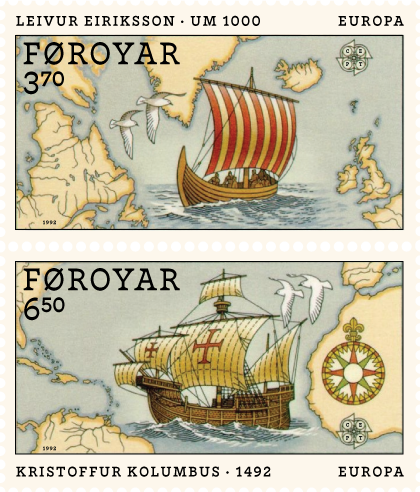

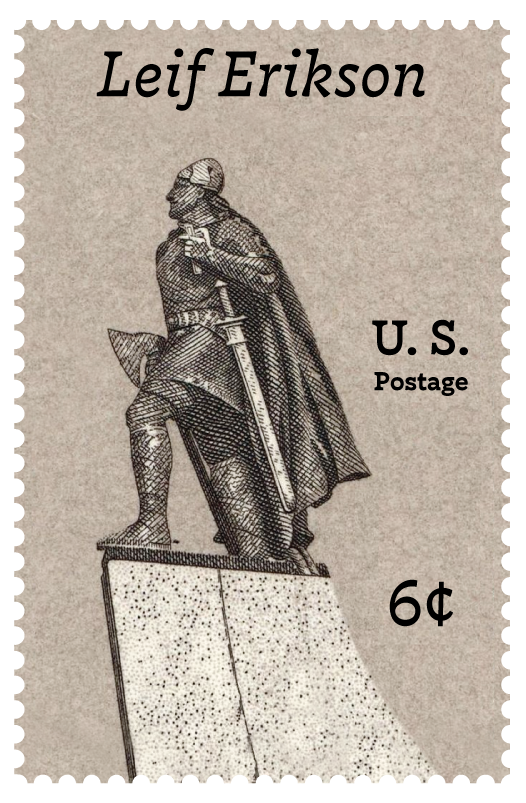

Eirikr’s son Leifr must have inherited his father’s lust for adventure. He went back to Norway in 999 to become a hirdman of King Olafr Tryggvason. There he converted to Christianity and was given the mission of introducing the new religion to Greenland. On his way back, he was blown severely off course and made landfall on unknown shores, a prosperous land of “self-sown wheat fields and grapevines”, no less than 3500 kilometres from Norway. Knowing he might have stumbled upon something big, he went back to Greenland, Christianised the people there, bought a big ship and went back to the land he had discovered with a crew of 35 men. He called it Vínland, because of the vines and grapes growing there. Today, we call it Newfoundland. Leifr Eiríksson had discovered North America, almost five centuries before Christopher Columbus. Long thought of as a myth, this discovery was proven beyond doubt when the Norwegians Helge and Anne Stine Ingstad found remnants of a Norse settlement in L’Anse aux Meadows in 1960.

So what became of the Norse people in all these newfound lands? The ones on Iceland and the Faroes are still there – after a thousand years, people still speak languages Leifr Eiríksson would have understood bits and pieces of. Shetland and the Orkneys were sold to the Scots in 1469, but the Norse heritage is still evident in place names, and there are still words of Norse origin in the local dialects. On Greenland, things did not go so well. The climate cooled considerably in the 14th and 15th centuries ("the little ice age"), and there might have been encounters with violent ancestors of the Inuits coming from the North. After Denmark seized Norway early in the 15th century, trade ships no longer sailed to Greenland. The last record of Norse people on Greenland was a marriage in 1408. When the Danes finally sent a ship in 1721 – not to provide food or supplies, but to convert any surviving Catholics to Protestantism – none were found. No permanent settlements were established in North America. Why is still unknown, though there are records of hostile relations with the indigenous peoples, using catapults. The Norsemen were few and only armed with swords, and wisely gave up the fight. Unlike the Spaniards and Portuguese who came later …

Our final postcard is a tale of bravery and curiosity. Thus, it makes a fitting finale for the

Nordvest Tour, our combined travelogue and digital type specimen showcasing a typeface unafraid of exploring new territory: Nina Stössinger’s Nordvest.